Who am I?

Monika Bode (Diploma in Museum Studies)

For more than four decades I am working at the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle (Saale).

After graduating, I took on the task of setting up visitor support and museum education at the museum. From the beginning, the focus of the museum communication was on experience- and sensory-oriented education.

I am particularly interested in the eating habits of our ancestors. Based on the results of archaeological research, I try to unravel the „kitchen secrets“ of prehistory through experimentation.

Cooking – the modification of food as encountered naturally – also influenced the social behaviour of our ancestors. The vital intake of food became a pleasure also through communal action.

"Der Mensch ist ein Tier, das kocht."

("Man is an animal that cooks.")

When it comes to the utilisation of animals this becomes particularly clear. Unlike today, our ancestors did not discard any parts of the animals they killed. In the truest sense of the word, animals were utilised from snout to tail.

Which parts of the animal were used and how?

- hide: clothing, containers, and straps

- bones: tools and food (bone marrow was particularly popular)

- horns, antlers: tools, ornaments, and containers

- tendons: bowstring, binding material, and sewing material

- meat: food – all parts of the animal not just the tenderloins

- blood: food

- offal: heart, liver, stomach, lungs, tongue, and brain were eaten. Intestines were cleaned and used as binding material and sausage casing. The bladder was cleaned, inflated, dried, and used as a container.

Alles, was wir über Ernährung und Zubereitung der Nahrung wissen, basiert bis zum Aufkommen schriftlicher Quellen auf archäologischen Funden und Befunden sowie den naturwissenschaftlichen Analysen von makro- und mikrobiologischen Resten.

Alle nachfolgenden Speisevorschläge wurden von mir getestet und an meiner Familie sowie Kollegen ausprobiert – alle leben noch.

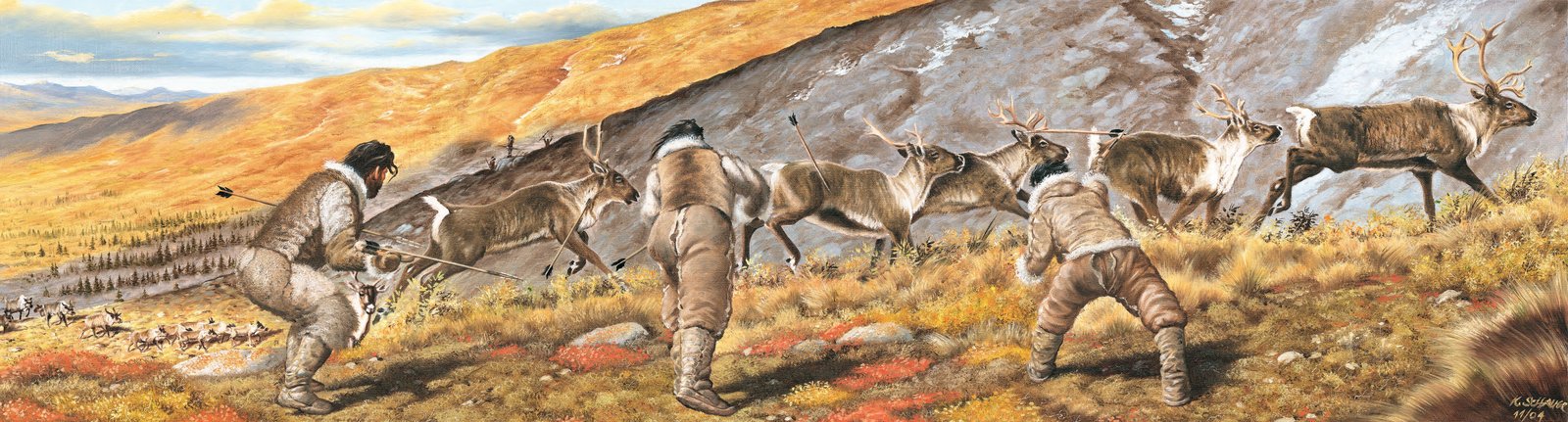

This phase of human history was characterised by cold and warm periods. The climate determined the resources of the habitat and forced people to adapt to nature and its conditions. They learned by observation and self-experiment.

In groups they hunted wild animals and gathered edible plants and their fruits. If the group was too large, it was split up. The size of the community and the “technical kit” determined the prey.

For processing food – usually on a piece of leather placed near the fireplace – flint implements such as knives and scrapers were used. The fireplace was the central element of cooking. Wood was collected for it and cooking stones were kept at the ready. For special dishes a cooking pit was prepared in which also whole animals could be cooked.

Many parts of plants were used as food – be it leaves, bark, or roots. The same applies to seeds, fruits, and nuts. Animals were hunted and the meat made edible in various ways. The diet had to be frequently supplemented with insects, shellfish, snails, birds and their eggs. Honey for sweetening and salt in the form of brine or crystals were used together with various herbs for seasoning.

The climate has changed. The major phases of the warm and cold periods were gradually replaced by the change of seasons with which we are familiar today.

Around 7,500 years ago, people from the so-called Fertile Crescent migrated to central Germany along the fertile loess soils, bringing with them a fully developed farming culture, including the first crops and domesticated animals. Cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs formed the domestic animal population. People established settlements, worked with stone, and made ceramic vessels.

What was used?

Equipment

Cooking and storage vessels made of clay, grinding stones, flint knives, clay baking plates, baking ovens, vessels and utensils made of wood and bark

Food

- cultivated: emmer, einkorn, barley, peas, lentils, opium poppy, flax

- hunted and/or kept: birds’ eggs, fish, domestic and wild animals

Some food was still prepared outdoors, but with hearths secured by stones and clay, earthenware vessels, and the baking oven, it was also possible to cook indoors.

The basis of the diet was most likely porridge, soups, and flat bread in the most varied of forms and with a wide variety of side dishes. They are easy to make and very satisfying. However, this does not mean that the three big B’s (bread, barbecue, beer) were dispensed with. Also pastries were prepared.

Now you have gained a little insight into the kitchen of the prehistoric past. I hope that I was able to provide you exciting and, above all, tasty suggestions that you can now try out for yourselves.

You are welcome to send me your photos and impressions. Maybe they will even make it onto this website – who knows.